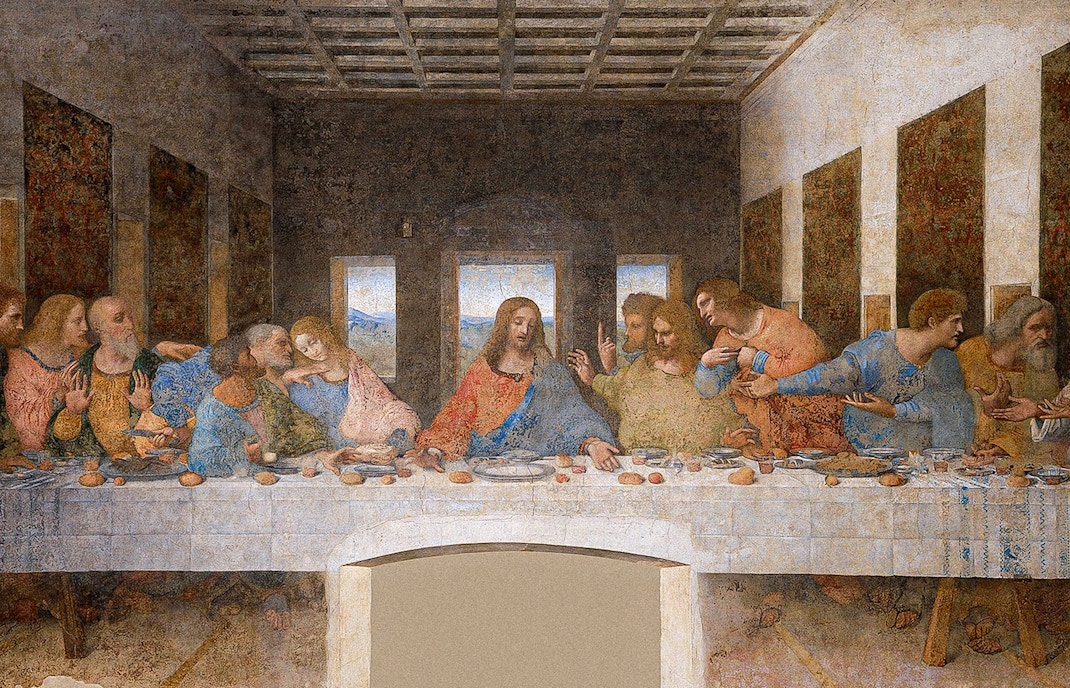

Traditional frescoes involve painting on wet plaster for a strong bond with the wall. But Leonardo da Vinci, always the experimenter, tried something different. He applied tempera (paint made with pigments mixed with egg yolk) on a dry plaster surface. Additionally, he prepared the wall with a special treatment to help the paint adhere. Working on a dry surface allowed da Vinci to take his time, add intricate details, and make changes to the painting as he went. This is evident in the incredible details and lifelike figures in The Last Supper. However, this unique approach led to the painting's slow decay over time.

Fascinating facts about The Last Supper mural

1. The Last Supper is not a fresco

2. Da Vinci used a hammer and nail to get the ideal perspective

The Last Supper isn't just stunning because of its subject matter — it's also a prime example of a one-point perspective. The way Leonardo da Vinci played with symmetry and angles gives the painting an almost dream-like depth. And here's the most interesting part: to nail that perfect perspective, da Vinci hammered nails into the wall and used strings to mark out the angles.

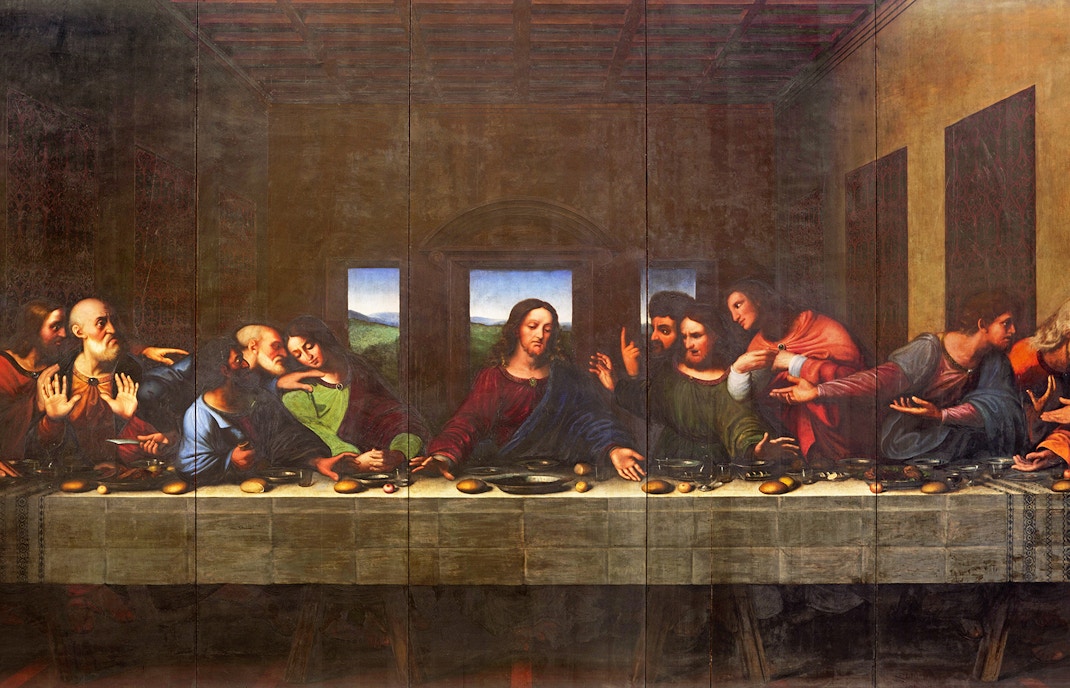

3. There are three early copies

Here’s a fun fact! There are three copies of The Last Supper believed to be made by Leonardo da Vinci's students. Giampietrino, one of his students’ copy in London's Royal Academy of Arts even helped restore the original after it flaked and deteriorated because it was painted in tempera and oil on a dry wall. You can also find copies by Cesare da Sesto in a church in Switzerland and Andrea Solari in a museum in Belgium.

4. Napoleon and his troops damaged the painting

Picture this: The lord's supper painting, already a bit worse for wear, had to endure yet another trial during Napoleon's heyday. When his troops invaded Milan in the 18th century, they turned the room it was in into a stable! Imagine the poor painting, enduring more damage amidst all that hay and horse hooves. It's a scene straight out of an art history drama!

5. The painting has also survived World War II

During the tumultuous era of World War II, The Last Supper encountered a formidable trial. A bomb ravaged the roof and a section of the wall housing the refectory, where Leonardo da Vinci's masterpiece resided. Despite the devastation surrounding it, miraculously, the painting endured. Its survival stands as proof to its resilience, weathering yet another storm of adversity and emerging unscathed.

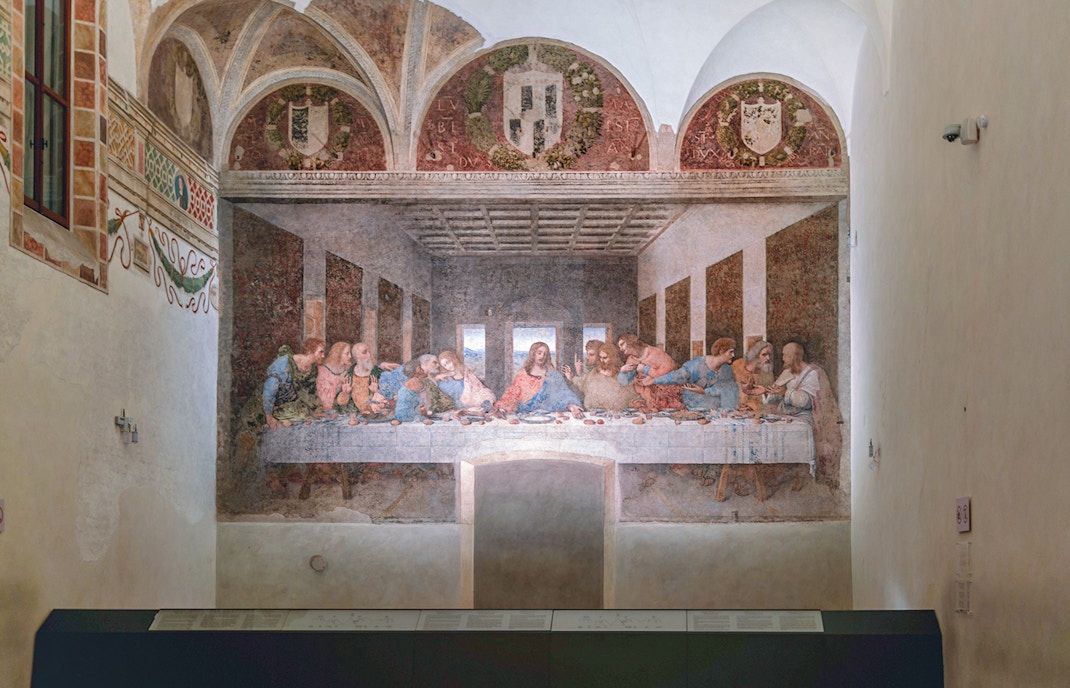

6. It is not displayed in a museum and never will be

The Last Supper is not housed in any museum. It is maintained in Santa Maria delle Grazie. The Last Supper is painted on the north wall of the refractory inside the convent. The refractory has been converted to a controlled room to prevent further deterioration of the painting due to environmental factors. Due to its large size of 460 cm × 880 cm (180 in × 350 in) and the fact that it's painted on a wall, it cannot shifted to a museum.

7. A portion of the painting is missing

Let's delve into a fascinating chapter of art history. In 1652, renovations were underway at the Santa Maria delle Grazie convent, home to The Last Supper painting. In an unfortunate turn of events, during these renovations, a decision was made to create a new doorway, resulting in a section of the painting being irreversibly damaged. Regrettably, this included the lower central part of the artwork, impacting the depiction of Jesus' feet.

8. The Last Supper makes Leonardo’s political statement

Art historian Michael Ladwein says that the painting is a subtle nod to its patron, Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan. Ludovico was quite a Renaissance man, supporting arts and sciences in Milan. Despite his cultural contributions, his reputation took a hit due to military campaigns and some perceived shortcomings during a time of internal strife. The painting holds within its strokes a secret tale of power, prestige, and the complexities of patronage in Renaissance Italy.

9. The painting is a pop culture phenomenon

The Last Supper has become a pop culture staple, making appearances in TV shows like The Simpsons and South Park, where it's used for comedic and satirical effect. Even dramas like The Sopranos and sci-fi series like Battlestar Galactica incorporate its themes of betrayal and faith. Sitcoms like That '70s Show playfully reference it, while action films like The Expendables 2 subtly evoke its imagery.

10. Only a few of da Vinci's real brushstrokes still remain

The painting went through a lot and has a history of abuse. The French Army threw stones and scratched the Apostles’ eyes. Restorers mistook it for a fresco, causing more damage. It's been touched up so much that the artist's work is barely there. Still, it remains a stunning sight.